Imagine an accessible nightclub

Deaf, disabled and neurodivergent people are designing their dream nightlife

Dear every body,

Welcome to the third edition of Body Babble! I hope you’re all well.

A few updates before we begin…

Priti Salian from the excellent Reframing Disability (also on Substack) published a lovely interview with me about my work. I’ve been a fan of Priti’s newsletter for several years so it felt very exciting to be featured. Have a read!

You may or may not have noticed that I’ve been recording audio versions of each newsletter. You can listen to these as a voiceover (above) or on Spotify, if that makes things more accessible to you (or you’re dying to hear me do ASMR).

If you enjoy this edition, please let me know! Like, comment, subscribe, share. I won’t know you’re reading unless you let me know you exist!

Today we’re talking about accessibility in nightlife. Given I ended my last newsletter with an ode to dancing (and the sign-off “See you on the dancefloor”), it seems only fitting that we’re now exploring how Deaf, disabled and neurodivergent people can participate in nightlife.

This is a topic I’ve become interested in over the last few years, as it’s become increasingly relevant to my own life. For a lot of my twenties, I was too ill to leave the house in the daytime, let alone think about going out at night! But as I approached thirty and my health and mobility were steadily improving, I found myself dreaming of the dancefloor. I say dreaming, because there was one slight obstacle: where to go?

My friends, who were beginning to settle down, were less inclined to go out than they were a decade ago. Nights catering to queer women seemed few and far between and anyway, I’d struggled to make a group of queer friends in my twenties because I’d been so unwell. And then there were the access barriers: how I had trouble standing still; my fatigue; the heat; the lack of seating.

I know I’m not the only one feeling the push and pull of the dancefloor. In the UK in recent months, a wave of events and initiatives are striving to make clubbing more accessible. I’m thinking of Deaf Rave, who put on club nights for the Deaf community. Or United by the Groove, which recently hosted Manchester’s first accessible rave. Or the subject of today’s newsletter, Dancefloor Intimacy, which encourages us to imagine our own nightlife utopia by asking: “What’s your dream accessible clubbing experience?”

By the end of this edition, I hope you’ll tell me yours.

In this edition of Body Babble, we’ll cover:

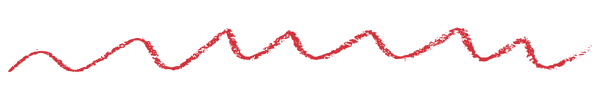

Why Ali Wagner set up Dancefloor Intimacy

What a Dancefloor Intimacy focus group looks like

People’s perceptions about disabled people and partying

Physical barriers and discrimination

What would an accessible dancefloor look like?

Communicating accessibility and giving people choice

The nightclub as a space for sex and politics

Why we need the dancefloor

Discovering Berlin’s clubbing scene

When Ali Wagner moved to Berlin, she threw herself into the city’s vibrant queer clubbing scene. Quickly, nightclubs became her “second home”:

“They’re somewhere where I’ve met so many of my cherished friendships. Where I’ve realised my queerness. Where I’ve learned so much more about myself.”

But while the club was initially a place for Ali to escape and experiment, at some point the lifestyle began to take a toll. “I loved it,” she says, “I was having the time of my life. But then I realised, ‘Oh fuck,’ I was doing that because I felt a certain way.”

While we might associate a Berlin clubbing scene with freedom, in reality Ali found it “super exclusive”. She felt anxiety in crowds, experienced aggression from men, and struggled with the fact that there was never anywhere to sit down. All she often needed was to be able to step away from the dancefloor, “chill” and have a conversation with someone:

“When clubs don’t allow you to relax at times and feel safe, some people can lean into abusing substances, and I realised that was something I was doing, because I was trying to cope with the fact that I was so overwhelmed.”

Putting accessibility at the forefront of club culture

40% of disabled people report being “unable” or having “extreme difficulty” accessing nightclubs or music venues. According to Ali, the problem is that clubs usually only consider accessibility as an afterthought:

“It’s like: ‘We’ve sold all the tickets, we’ve designed the event, we’ve invited everyone to come.’ And then: ‘Oh, well, how can we make this more accessible?’ And I think my dream is that it’s something that actually inspires events and inspires design.”

As part of her final-year thesis, Ali began to research how neurodivergent people experience nightlife. But when she received a grant from her university, she was able to expand that research to include more people:

“There are so many disabled individuals, neurodivergent, Deaf, blind, chronically ill individuals, who can’t access or don’t feel safe or welcome in these spaces. Or they don’t have anyone to go to these spaces with.”

She launched Dancefloor Intimacy: a movement that puts accessibility at the forefront of club culture. The initiative runs focus groups with disabled people, and those who attend are paid a stipend (most recently, they’ve been working with London’s iconic Fabric).

“My purpose is to be the facilitator,” says Ali. “The disabled ravers are the ones actually making the change. They’re the ones giving their honest opinions and insights.”

People don’t think disabled people want to party

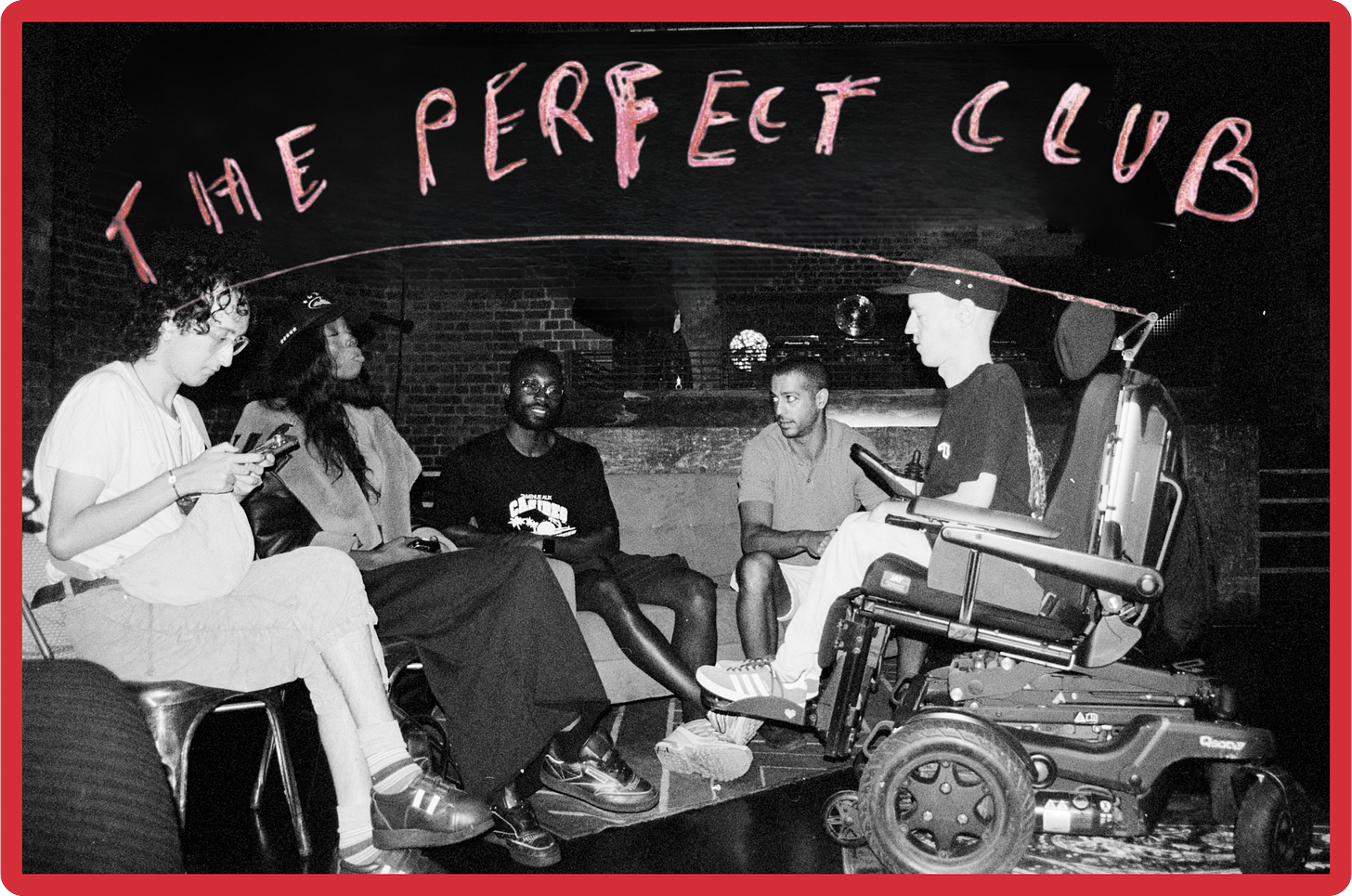

At a Dancefloor Intimacy focus group, half a dozen young disabled people are sat around a table, armed with pencils, paper and crayons. Behind them, text on a big screen asks “What is your ideal accessible clubbing experience?”. If it’s refreshing to be asked this, it’s also a little jarring—it’s hardly a question you hear every day.

“People don’t think that disabled people want to go to clubs and festivals,” says Ali. Although this is partly because of physical access barriers (wheelchair-users “can’t get through the door”), it’s probably also because up to 80% of disabled people have a non-visible disability.

Tatum, a creative and producer with muscular dystrophy, is one of the focus group’s participants:

“People think, ‘Oh, disabled people don’t want to be here, because we don’t see them.’ So then access isn’t implemented, so disabled people can’t come, and the cycle goes around. But when access is actually put in, you see how many disabled people turn up.”

Dealing with other people’s perceptions

Katouche, a content creator with cerebral palsy, is also one of the group’s participants. She “loves a night out, every part of it” and enjoys “the breadth of urban music”, from R&B to Afrobeat, rap, bashment and soul.

But when she goes clubbing, “people can point and laugh”:

“You are a spectacle. In general you don’t see visibly disabled people in public life. And I feel like the nightlife scene is a microcosm of the power and social dynamics that exist in society. So people are quite astonished to see a disabled person in the club.”

Tatum, who uses different mobility aids on different days, often gets intrusive comments from strangers. Using a walking stick, they get comments like: “‘Oh God, you’re that old already?’”. And when they use their wheelchair, “people either try not to acknowledge me or they’re like, ‘Oh, it’s so cool that you’re out.’”

Discrimination at the door

Katouche’s experience of going clubbing is further complicated.

“There’s layers to it,” she explains. “Especially when you’re dealing with a community within a community. There’s no regard for Black disabled people, especially Black disabled women.”

As well as being refused entry on account of her disability, Katouche has experienced racism on the club door. And it’s hard to find venues which feel welcoming or cater for Black disabled people:

“The venues that have access aren’t typically venues that would play the music that I would enjoy. And the venues that play the music I enjoy don’t typically have access.”

And she adds:

“And the venues that have access and have the music I’d enjoy don’t allow Black people in the venue.”

Getting onto the dancefloor

As well as discrimination on the club door, there are often physical access barriers to getting inside. Sophia, a disability advocate and wheelchair-user, is another a participant in the focus group. Though she “loves to dance” and enjoys salsa, reggaeton and R&B, she says:

“I usually end up dancing in the street or at home, because unfortunately finding a club is difficult. Traditional clubs tend to be in basements or up stairs.”

Tatum describes the lack of physical access as a “gut punch”:

“I either can’t get into the venue at all, or I’m sent round the back, away from my friends, down some sort of service lift. And when I get in, I can’t access all of the space anyway. Or I can’t get through on the dancefloor.”

Because of this, Tatum sometimes chooses to go to the club without their wheelchair. But this has consequences:

“If I’m not in my wheelchair the whole time I’m on a dance floor, I’m having to think about keeping upright. I’m in so much pain that I can’t really have fun.”

What would an accessible club look like?

So what would it look like if the dancefloor were accessible? If every disabled raver could not only get through the door, but get a drink, go to the loo, have a dance or make out with a stranger?

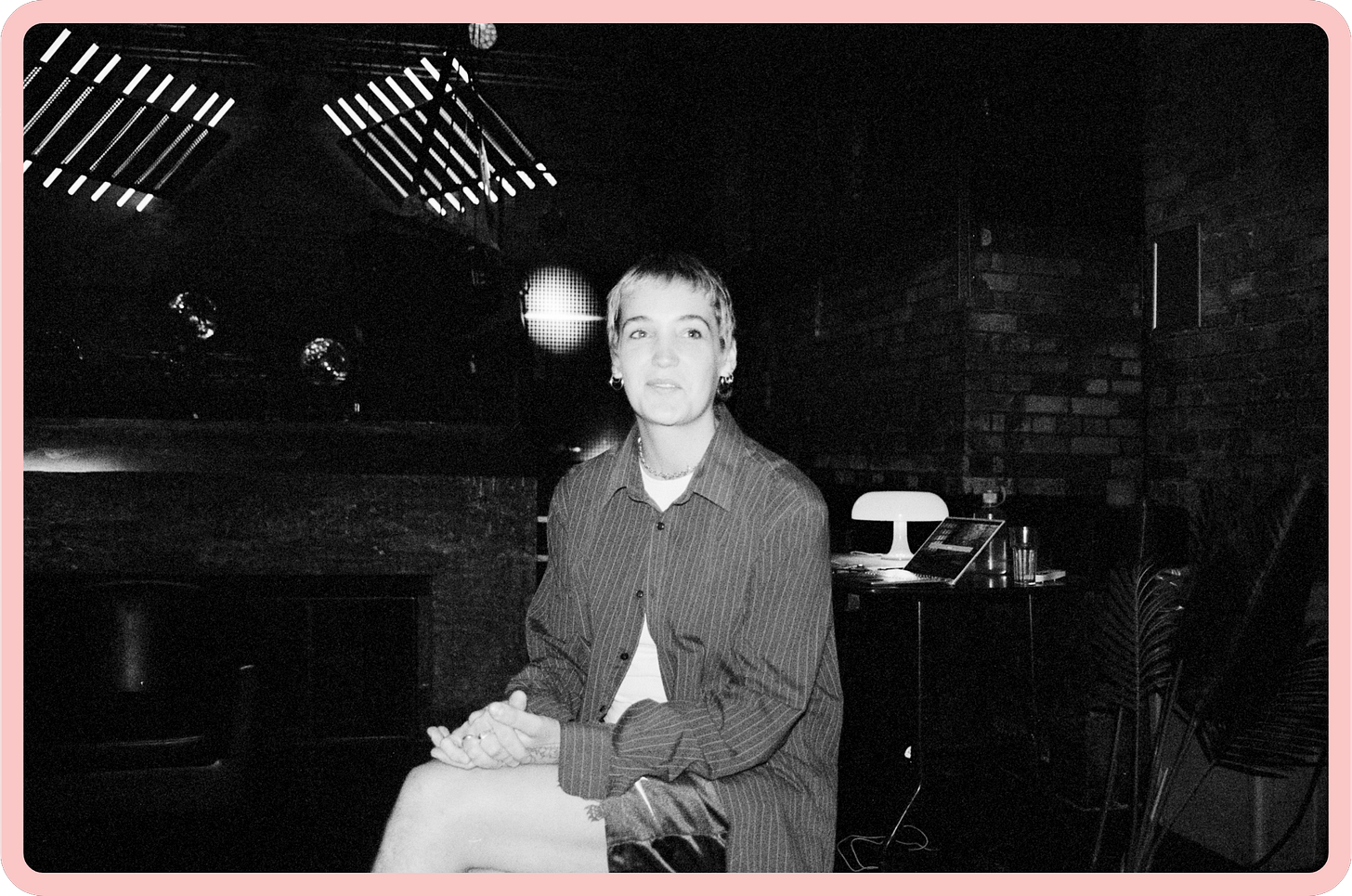

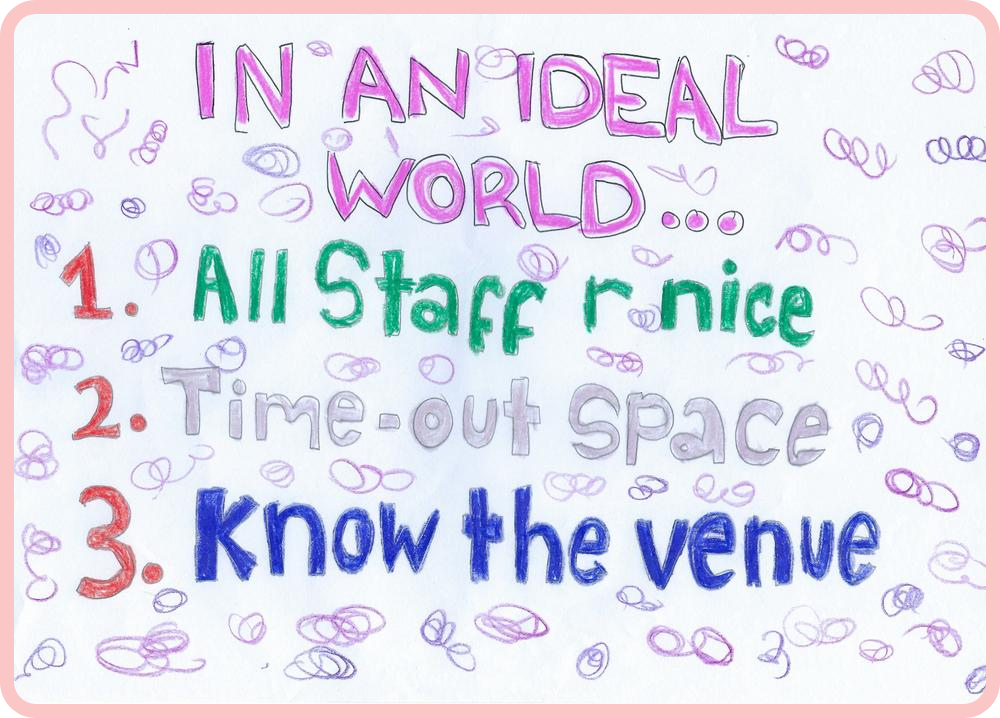

This is the part of a Dancefloor Intimacy focus group where participants get out the colourful crayons and sketch their dream clubbing experience.

“We were trying to picture what’s realistic,” says Tatum. “But also: what’s our utopia? Why not strive for utopia?”

Some access needs are pretty universal. Everyone wants affordable tickets, ramps, lifts, accessible toilets, good local transport links, and friendly staff trained in disability equality. But others imagine something more specific.

Tatum says, only slightly in jest, that their dream music festival would just have:

“Food trucks. That’s my utopia.” But they add, on a more serious note, “I have chronic fatigue, so I need to keep my energy up,” and that disabled people should be able to skip long queues for food.

One of the biggest challenges of a night out, for so many of us, is the lack of seating. Even if we can dance for a while, most us would have more endurance if we could pace ourselves and also sit down.

“I’m not going to pay £20 on your party knowing there’s nowhere for me to sit down,” says Ali. “That’s not how I want to spend my Saturday night.”

Tatum suggests a solution:

“Say there’s not a lot of space to have chairs, on the walls of a space [you could] have pull-down chairs that can go back up again.”

Lots of people also mention the need for “time-out space”. Nightclubs are invariably hot, noisy, crowded, and overstimulating, so especially for people who are neurodivergent or chronically ill, having somewhere to decompress and step away from the dancefloor would make all the difference.

Giving people the choice to decide

One challenge of designing accessible nightlife is that sometimes people’s access needs conflict. Ali explains:

“Some people are like, ‘Oh, I love strobe lights. And then other people are like, ‘I hate strobe lights.’”

In people with conditions like epilepsy, strobe lighting can trigger seizures, so in this situation the priority would clearly be to prioritise people’s safety over personal preferences. But in many cases, the solution to conflicting needs is “giving people lots of options.” Ali explains: “I think accessibility is ultimately all about choice and transparency.”

For Sophia, transparency is crucial. An accessible night-out isn’t only about physical access, but about being given enough information so she can make a reasonable judgment on whether or not to go.

“Clubs, venues and bars should have the accessibility information on their websites, even if they don’t have good access. For example, there’s a place called Scala, and although it’s an inaccessible building, they say how many steps there are to get into the building, so it leaves it up to the person to decide whether they can access it or not. Whereas if you have no information, it just leaves you feeling really deflated.”

Providing detailed accessibility information ahead of an event means, for example, describing whether there’s full wheelchair access, seating, or if the venue is near step-free local transport. But the more detail, the better: ideally they should also say, for example, how many steps there are, give measurements of door widths, and provide photos or videos of the inside and outside of the venue (yes, even the toilets).

Being open and willing to help

For Katouche, being transparent and giving people choice can go a long way in compensating for a lack of physical access:

“There’s accessible versus being accommodating. Some places may not have the logistics or the structure, but they’re open, they have a willingness to want everybody to enjoy it.”

She explains:

“I’ve been to venues where they’ve been happy to carry my mobility scooter down the stairs and make sure I have somewhere to sit when I’m inside, or they find me a table.”

Ali agrees that the most important thing is “just being honest” about how accessible a venue or event really is. For example, she’s hosting a party this weekend in the warehouse she lives in:

“It’s up three flights of stairs, it’s an old factory space,” she says. “So we’ve made it clear it’s on the third floor so it’s not step free access, but you can email us, and if you’ve got mates who want to carry you up or down the stairs, and we can do that in a safe way, then let’s try.”

Pleasure and politics

Jane Madden recently completed an MA in Disability Studies at the University of Leeds. Her research, titled “Campaigning for a Good Fuck: The Fight for Inclusive Nightlife Spaces”, argues that inclusive nightlife is not just about access to dancing but about disabled people’s sexual citizenship: having opportunities for flirting, romance and sex. She explains that “disabled sexuality is very much neglected”, even within the disability rights movement, which so often focuses on education and employment.

When Tatum moved to London aged 18 they were finally able to explore their queerness:

“I wanted to snog a woman on the dance floor! Clubbing gives you that experience where you can try things out.”

Meanwhile, Ali believes nightlife can build empathy. When you meet different people and share an experience on the dancefloor, you “walk back into your different lives and take that with you.” At a recent event she hosted, she invited her trans friends to do a performance in which they had “these really big protest signs”:

“What I loved the most was seeing all these amazing straight men on the dancefloor, who afterwards were saying how beautiful they were and asking questions about trans rights.”

“Nightlife is political,” says Tatum:

“I think the powers that be would rather us stay home, spend money online and not talk to each other. But dance and music are part of resistance because we’re expressing ourselves and we’re sharing joy, but also we’re talking. We’re chatting about what’s going on in the world. We’re organising.”

The nightlife industry is struggling

I’m torn between fantasy and reality. During my conversations with contributors, I get lost in dreams of an accessible dancefloor. But then I go on Instagram, come across a night I want to go to, and I’m reminded: nightlife is still overwhelmingly inaccessible, and access isn’t top priority in an industry which is already on its knees.

Over the last five years, more than a third of the UK’s nightclubs have closed. We’re all familiar with some likely explanations: the cost of living crisis, people’s lifestyles changing after Covid, and Gen-Z drinking less than previous generations.

Queer venues, especially, are struggling, and more than half of London’s LGBTQ+ venues have closed since 2006. This is bad news for disabled people, not only because we’re more likely to identify as LGBTQ+, but also because many of us find queer spaces to be more accessible anyway.

“When I go into straight spaces, it’s shocking how much more ableism I experience,” says Tatum. Sophia agrees that when it comes to accessibility, the queer community “is making much more progress.”

Why we need the dancefloor

It’s interesting that queer spaces should feel more accessible when they have more than their fair share of physical barriers: usually they happen on small budgets or at grassroots level, with a DIY spirit. They’re in basements or warehouses, if they even find a permanent home at all; often they operate as “pop-ups”, hopping from venue to venue. None of these things are exactly a recipe for physical accessibility.

So is it an attitudes thing?

Certainly in my experience, within the queer community there’s less shame in straying from expectations, more of an open, honest conversation about our bodies or limitations, and a willingness to do things differently. But perhaps it’s also a history of persecution which has taught us to embrace joy—to know how much these moments matter.

Clubbing offers us a kind of transcendence, says Tatum:

“You’re just being with the music and looking into your friend’s eyes and smiling and feeling that euphoria.”

But to get to that feeling, we can’t only scheme. At some point, we have to take the leap. We have to go out, onto that inaccessible dancefloor, knowing there will be barriers and people who stare, but trusting that it will be worth it. That the joy will outweigh the pain.

Because dancing with strangers in the messy, real world is always more fulfilling than polishing a dream.

“Right,” says Sophia, “So when are we going dancing?”

I’m ready when you are,

Celestine

Thank you…

Photos by Lydia Garnett and Solar KBD, via Ali Wagner.

A huge thank you to Ali for sharing so much with me about accessible nightlife and Dancefloor Intimacy. Thanks so much also to Katouche, Sophia and Tatum for being so open, wise, and honest with me about your experiences of going on nights out. Thank you to Jane Madden for sharing your interesting research.

Thank you to Theodore Fraser for editing.

More disabled joy!

Just found your Substack today and already really enjoying it and learning a lot. Thank you!