When you stammer with someone

At Stammering Pride, dysfluency creates connection

Dear every body,

Welcome to the first edition of Body Babble!

Today we’re talking about stammering. Stammering, or stuttering, as it’s known more commonly in the U.S, is a speech “disorder” which creates a difference in the way people speak. According to STAMMA, the UK’s largest stammer charity, people who stammer repeat sounds or words (“My name is J-J-J-John”), stretch or prolong sounds (“Can you tell me a ssssstory?”), or have a silent block where a word gets stuck (“----Can I have…”).

I don’t have a stammer myself and until recently, I can’t say I’d spent any time thinking about stammering (at least not since I watched The King’s Speech back in 2010).

But in late July, I found myself at a poetry night in a bookshop in South-East London. I arrived slightly early, and the poets were still sound-testing the mics, so to pass the time I browsed the books, bought myself a beer, and sat down next to a friendly young guy with red hair who introduced himself as Patrick.

We got chatting and quickly found common ground. We talked about our favourite poets, about Frank O’Hara. We talked about how—and what a coincidence—we were both involved in the small world of disability arts. Patrick mentioned in passing that he’d written a book—about stammering. “Stammering?” I said, bouncing on the word. Did Patrick have a stammer? If so, I hadn’t noticed.

And then the poets performed; the audience whooped, clapped and whistled. Afterwards, at dusk, the air still warm, we lingered on the street outside, talking. At some point Patrick’s stammer revealed itself. But it was getting late, and before long we exchanged Instagrams and goodbyes.

The next morning, I woke to a DM from Patrick with a link to a Frank O’Hara poem. “And,” he added, “another thought”: did I want to join him on Saturday at Stammering Pride?

In this edition of Body Babble, we’ll cover:

Stammering Pride

Songs that stammer (feat. Poker Face, Changes, Lola, My Generation)!

What it means to have a “covert” stammer

The medical model vs. social model approaches to stammering

How stammering can be a source of creativity

How we can better support people who stammer

What stammering can teach us about connection and relationships

It’s a Saturday in August and the sun is shining in Victoria Park, East London. Couples clutch their coffees and cockapoos, cyclists dart past, and twenty of us are marching down the broadwalk, waving stripey blue flags and chanting: Stammering Priide, Stammering Priiiide, Stammering Priiiiiide!

We’re getting louder, gaining confidence as we march, emboldened by our strength in numbers and brazen to the confusion on strangers’ faces. At some point Patrick suggests we add a stammer to our chant. We find a rhythm. Sta-sta-stammering P-P-Pride! Sta-Sta-Stammering P-P-PRIDE! STA-STA-STAMMERING P-P-PRIDE!

Passers-by are looking at us. They’re looking, I suppose, at the size of our group, or at our signs and placards, or at the blue flags we’re waving (What country is that? Has the LGBTQ+ Pride flag been updated again?), or maybe, and this is the most likely explanation, because Patrick is blasting music out of a sound-system.

We're shuffling through a playlist of “stammering songs”. There’s Lola by the Kinks. Changes by David Bowie. Lady Gaga’s Poker Face. But it’s My Generation by The Who that takes the crown as Patrick’s favourite. “It’s a really harsh stammer!” he shouts to me over the chorus (People try to p-put us d-down), “It’s the most realistic. It’s very powerful.”

We sit down at a group of picnic benches, in a clearing between the trees. Our tables are heaving with children’s party food —doughnuts, crisps, fizzy drinks and chocolate— as if pride would be impossible on an empty stomach. Some people have come with placards, which they’ve propped against a nearby tree: EMBRACE THE STAMMER, one reads, with hand-drawn hearts. Most of us are wearing shades of blue: teal and ultramarine are the colours of the Stammering Pride flag.

We chit-chat, talk about how far we’ve travelled, why we’re here. I confess, somewhat sheepishly, that I don’t have a stammer; that I’m just here to learn and support. Between bites of one explosive jam doughnut, I wipe the sugar from my lips and muster the courage to ask questions.

Mudassir is from Pakistan, but moved to the UK two years to complete a post-doc. Gina, from Bristol, is a writer; her biography of stammering musician Scatman John will be published in 2026 by Bloomsbury. Josh is a medical doctor, specialising in end-of-life care.

But everyone has come to Stammering Pride for similar reasons.

“I don't realise how much tension I'm under until I come here,” says Gina.

Mudassir is nodding. “It’s like, ‘Oh,’” he says with a deep breath, “You are relaxed.”

Facts about stammering

For Josh, Gina and Mudassir, moving towards pride in their stammer —or at least acceptance— has not been linear, but a lifelong journey.

Stammering usually starts in early childhood, and as many as 8% of children stammer. But although stammering affects equal numbers of boys and girls, girls are more likely to stop stammering. In adulthood, 75% of people who stammer are men.

A common misconception is that stammering is caused by nerves or anxiety. In reality, while anxiety can exacerbate someone’s stammer, research has shown that stammering has a genetic component (60% of people who stammer have a family member who also stammers) and that there’s a slight difference in how the brain is wired in people who stammer.

While Mudassir agrees that “If you have more fear, you’ll stammer more”, he insists that anxiety alone isn’t the cause of stammering. For example, at five years old: “I have no fear but I stammer.”

Stammering at school

In childhood, Mudassir, Josh and Gina experienced a pervasive shame. Mudassir remembers school as a place where “you feel bullying, too much bullying, I can't speak in the class because of the bullying.” Being asked to read out loud in class would make him sweat and shake with anxiety. “It was so hard,” he says, “So hard.”

“I was supposed to go to Oxford to read English,” says Gina, “But then I skipped every single class that had anything to do with reading out loud or doing any presentation. It was like ssself-sabotage.”

Josh is nodding. “I had a covert s-stammer at school,” he says. “I got good grades, I got four A-stars, I was in the sports teams, I did music. I was a successful boy, right? I didn't want to break that.”

What does it mean to have a covert stammer?

“It's c-c-characterised by avoidance,” says Josh. “Avoidance of words, of situations, of sounds or anything that is going to trip you up.”

It sounds a bit like masking, I say. Like when autistic people try to pass as neurotypical?

“Yeah, that’s probably the way of describing it that's easiest for other people to understand,” says Gina.

Josh agrees: “You’re trying to pass as fluent.”

During our conversation, Mudassir, Josh and Gina frequently refer to “fluency”, or being “fluent”—words I’d previously only heard applied to learning foreign languages. I soon learn that these are used as shorthand for speaking without stammering, or for people who don’t stammer.

Hiding who you are

Substituting words and going to great lengths to avoid stammering can have profound consequences on a person’s relationships, professional life and sense of identity. Josh explains:

“At the beginning it might just be a few little words, but then the more there’s a fear of the word, the more there’s a fear of making the mistake. […] And so you end up in a position where you go to order a sandwich from a café and you're worried about saying the word “ham”. And so rather than order the ham sandwich, you order the cheese sandwich. And that bubbles into every relationship, because now you're not being authentic. You're not saying what you want to say. You're saying what you can say and what you can get away with saying.”

Gina agrees: “I used to think I'm a shy person, but I don't know if that's true anymore. It's like, did that come first or is it just a result of all the hiding?”

Unfortunately, some words simply can’t be substituted, and these are often the words that stammerers struggle the most with.

“You can't substitute your own name,” says Josh. “You can try! But you look like a complete maniac. Or you look like you actually f-f-forgot your name. It's like, “Oh, you didn't know your name.” And it's like, “No, I have a stammer, man.”

Before Pride

Though speech and language therapy can help people manage their stammer, there is no known cure for stammering. Despite this, most people seem at some point to have fallen down a medical pathway.

While some people find speech or language therapy to be helpful, others find the way it often focuses on self-improvement to be harmful. Meanwhile, online, Gina says “there's a lot of people on YouTube saying they have a cure.”

Mudassir has seen those videos. “I think there are some techniques,” he says. “Like ‘prolongation’ and to take a deep breath and then make relax. But it is a long journey.”

Laura, originally from Romania, is a user experience researcher. She spent years in stammering support groups, but found even those “quite medical” and “oppressive” in their approach:

“They were focused on fixing your stammer and changing yourself. But when the pandemic came and it was something you don’t have control over, I realised that, okay, those stammering groups were t-t-t-taking a lot of time for me because I had to put a lot of work into controlling my stutter. And they were very much a losing game because I was still s-stuttering at the end of the day.”

Discovering the social model

Naheem, a healthcare consultant from London, was so determined to “get rid” of his stammer, he completed a whole neuroscience PhD on the topic:

“My whole thing was using electrical brain s-s-s-stimulation to try and enhance the areas of the brain involved in speech so that people who stammer would stammer less,” he says.

But after finishing his PhD, Naheem’s “view started to change”. He’d started his own stammering support group in London, had become more involved with the stammering community and had even joined the board for STAMMA UK. Crucially, he’d learned about the social model of disability: “It's not the stammer that's the problem, it's the effect it has on the quality of life and the choices a person makes in their life.”

For Laura, shifting from a medical to a social model view of her stammer was transformative. It allowed her to stop taking on so much responsibility and to surrender the self-blame:

“[Previously] if I had a negative encounter with someone, it was my fault because I didn't control my stammer. It was not perhaps because that other person was ableist and didn't give me enough time and interrupted me mid-sentence.”

Seeing stammering as a disability

Kristel is a speech therapist who’s flown to Stammering Pride from New York City. Though she spends her days supporting other people to accept or embrace the way they speak, she admits it took her a long time to feel pride in her own stammer.

Kristel also has cerebral palsy, and she witnessed a lot of ableism within the stammering community:

“It used to hurt my heart the way the stammering community was so against the thought of being a part of the disability community. It felt like they didn't want to be a part of that group. ‘That's gross’: that's the feeling I got.”

But she says that in the last decade the stammering community has begun to position itself within the wider disability movement: “All of a sudden everyone started talking about disability.”

“I think people realised they could use [the label ‘disabled’] at work,” says Patrick, explaining that identifying as disabled makes it easier for people who stammer to ask for reasonable adjustments:

“Often people who stammer really don't like if you get five minutes for an interview. That's really difficult and puts lots of pressure on your speech—it's unfair. So suddenly we were relying on the disability equality laws to try and change that.”

Josh learnt this through trial and error:

“I did some professional exams recently and I failed the first time and then I did them again and I passed. And the first time, having made all this peace with stammering, I decided not to identify as disabled: I didn't get any extra time. But the next time, I applied for extra time: I said I had a disability. And I found identifying as disabled was just that step of acceptance.”

Gina describes herself as disabled because it “offers protection against discrimination because of the way you s-s-speak.” She explains: “You may not identify with the word disability, but […] it offers protection against what is an unfair and ableist world.”

Giving people more time

We live in a world of TikTok and TED talks, which rewards hyper-fluent, fast-paced speech. Laura explains:

“Unfortunately, time is money in this current social economic environment. People want things to be as efficient and timely as possible. If we can do sssomething in the short amount of time, that's a win. But that doesn't work within the stammering world.”

If people are disabled by their stammer only because we live in a society that rewards hyper-fluency, what we can do to remove barriers and better support people who stammer?

“So I think the first thing is don't finish sentences,” says Patrick.

“Often people feel this need to rush in and finish a sentence. But I think just be relaxed when somebody stammers and not respond negatively. And think about the conversational landscape, and whether things are really time-pressured or not.”

Kristel agrees: “Just be patient and listen to their message and not worry so much about the fact that they're stuttering. Some people just need a little more time.”

Laura wants people to understand that stammering is more common than we think—and a natural variation on the vast spectrum of human speech:

“Just hang out with us. Just come and hang ouuut. For example, let's say that in this s-s-sssituation you might be hearing more stammering, so stammering becomes more normalised in terms of the way it sounds. You meet different people who you might not have clocked as having a stammer. […] We expect people to speak fluently by default, but many people don't.”

Kristel agrees: “I think the general population need to understand how stuttering is just a way that some people talk.”

In his book Words Fail Us, Jonty Claypole argues that stammering should be re-framed not as a disorder but as a difference—similar to how the neurodiversity movement has re-positioned autism, ADHD, Tourette’s, etc.

This reframing also helps to organise the community and to create a sense of collective identity: a culture with its own distinct art, inside jokes and shared experiences.

Stammering culture

Patrick is taking books and magazines out of his tote bag and laying them out on the grass. An eighteen-year-old girl has just arrived, her mother in tow. It’s the girl’s first time at Stammering Pride, and Patrick wants her to discover the rich culture that can come out of this community.

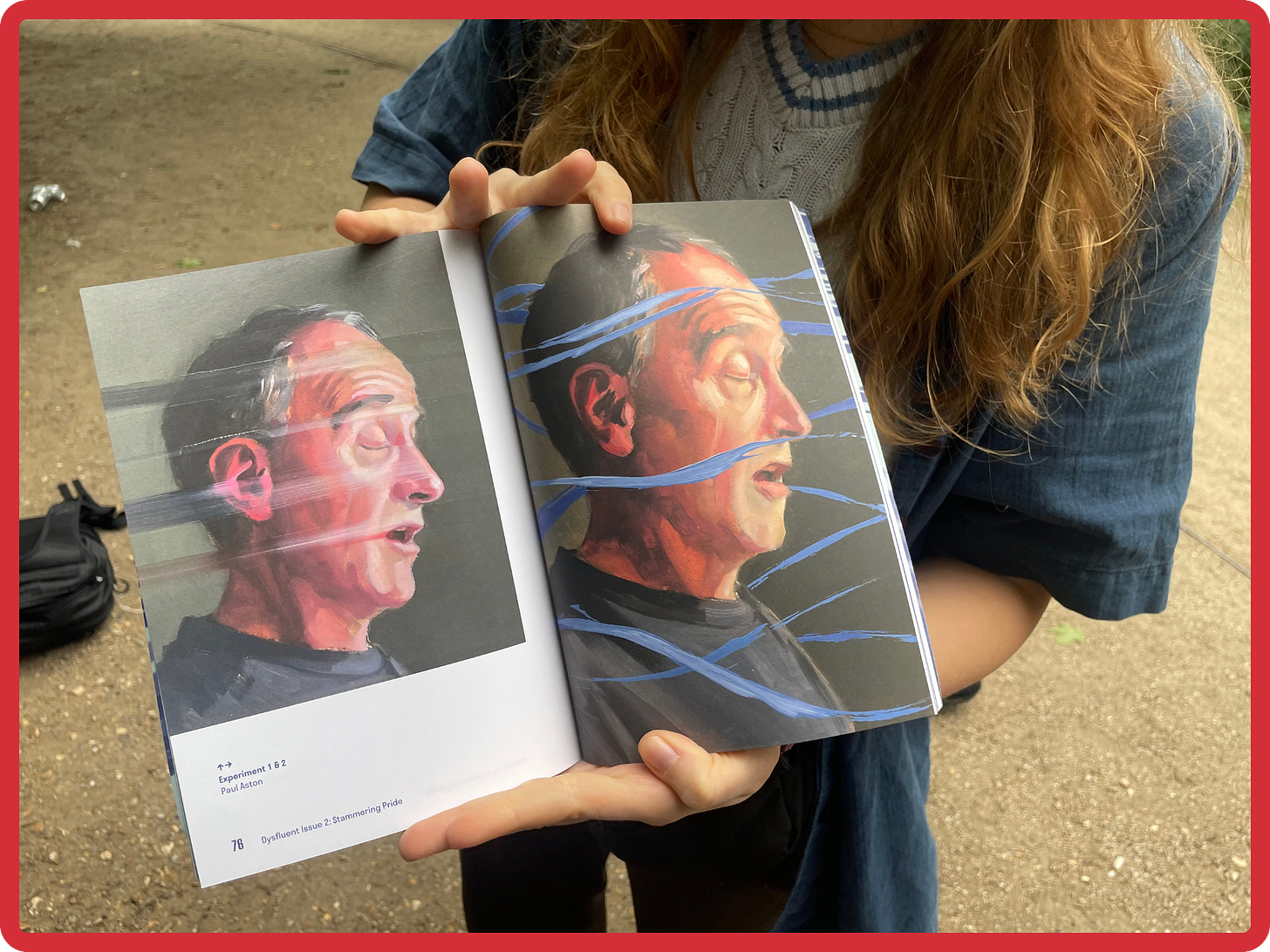

Dysfluent is an independent magazine which explores the lived experience of stammering. Started by designer Conor Foran, the magazine is bold and beautifully designed, experimenting with layout, the repetition of words, fonts and formatting to visually represent the experience of stammering on the page.

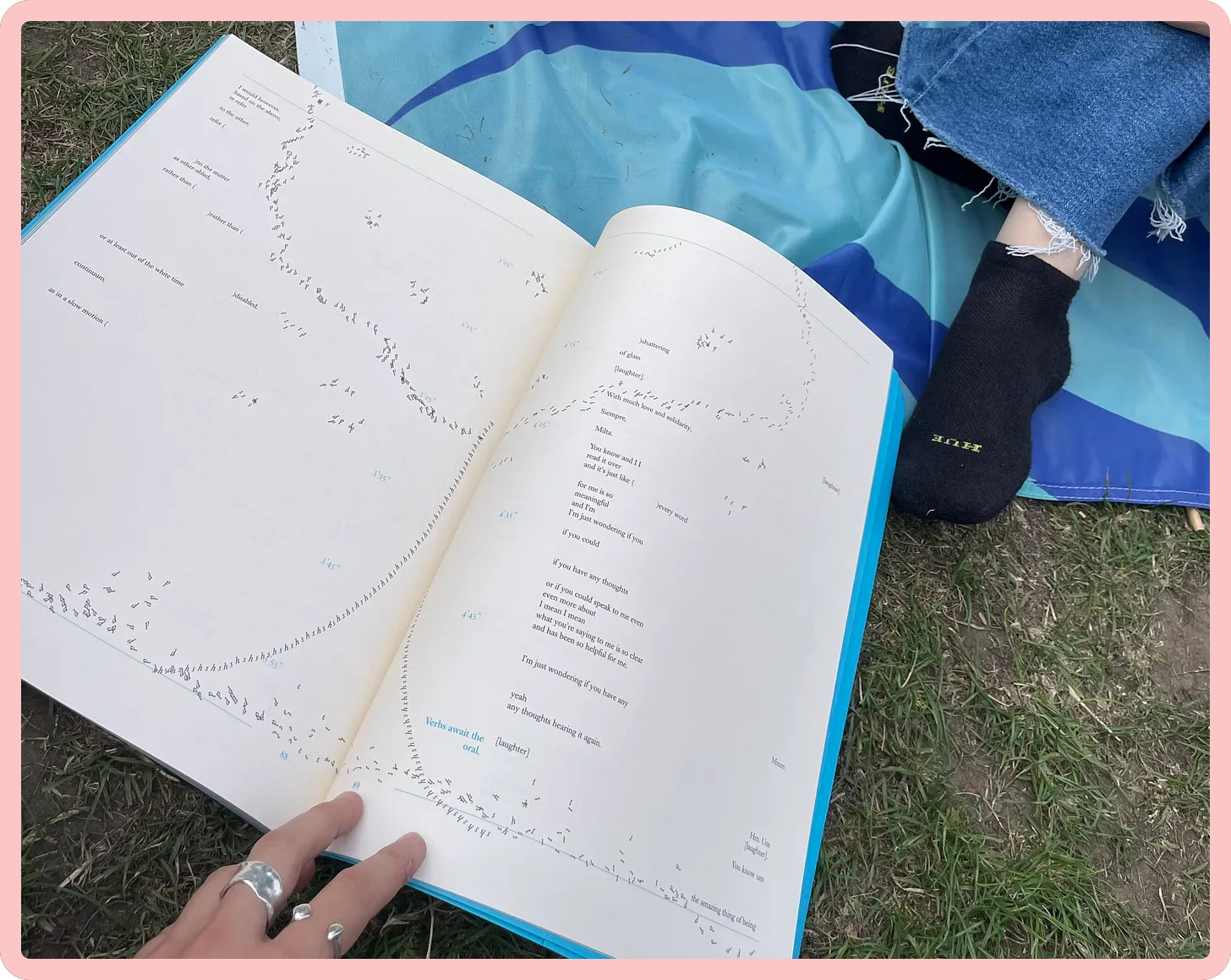

At our feet is also The Clearing, a book (and album) by artist JJJJJerome Ellis, an artist who spells his first name with five J’s “because the word I stutter on most frequently is my name.” Inside the book, the formatting is deliberately disruptive: letters and syllables look like they’re falling off the page, almost as if they got displaced by a gust of wind.

I’m intrigued by Claypole’s conviction in Words Fail Us that the experience of stammering leads people to “unique forms of creativity”:

“The language of stuttering is defined by its ornate and sophisticated synonyms as much as its blockages”.

Certainly, Patrick, Josh and Naheem seem to have managed to marry their own experience of stammering with their creativity. They share a love of poetry, and sometimes perform their own work at open mic nights. Inevitably, their stammers become part of their delivery, but what’s perhaps more surprising is the intimacy this can create with the audience:

Josh explains:

“There's this sort of amazing potential in the moment of the block, like anything could happen. And then when the block's over, there's a completion. You get this series of ruptures, of openings, of what could be, then a resolution—in a way that you wouldn't get if you just listened to someone [who didn’t stammer].

Patrick continues:

“That's why JJJJJerome called his book The Clearing. The idea is that when you stammer with someone, you step into this clearing. It’s a kind of mood, for a moment, that opens up.”

Relationships take time

On the train home from Victoria Park, I realise that stepping into that clearing has opened up something for me too. As a perfectionist, and as someone who’s felt plenty of shame around my own disability, I feel moved and quietly changed by my time at Stammering Pride. The people I met taught me that when you allow yourself—when you’re brave enough—to be truly seen, you’re often rewarded: with authenticity, connection and friends who give each other the time. I suppose this is a lesson for us all.

Patrick, Josh and Naheem are soon going to be moving in together. “It’s a very stammering-friendly flat,” Patrick laughs. They met years ago at stammering events but have, until now, never all lived in the same city at the same time.

They know each other “through stammering”, of course, but also through shared experiences, through patience, laughter and mutual vulnerability, and through showing up, year after year, at the conference or picnic in the park.

Our culture might reward hyper-fluency, but in relationships, there’s no x2 speed; no skip; no shortcut. It takes a while to know each other.

We get there, with time.

See you again soon?

Celestine

Thank you…

A huge thank you to everyone who welcomed me at Stammering Pride. I’m especially grateful to Patrick for inviting me into this world, and to Naheem, Josh, Mudassir, Kristel, Laura, Gina, Joe and Marilena for being so open about their experiences of, and in, stammering. Thank you to Patrick Campbell for proofreading and advice, and Theodore Fraser for editing.

I also learnt from Dysfluent Magazine ed. by Conor Foran, Words Fail Us by Jonty Claypole, Stammering Pride and Prejudice: Difference Not Defect, ed. by Campbell, Constantino and Simpson, and STAMMA.

This was really interesting. Thank you for introducing me to Stammering Pride! Thank you for also making your articles in audio format.

This was awesome! I learnt a lot & smiled a lot. Thanks Celestine, Patrick, & co.